Translated by: Yasmine Zohdi

“I do not think there is such a thing as a victory even for the rich. … I think we have got to stop thinking about victories and start thinking about how the hell we are going to live with each other, how are we going to live with the world we have inherited and the world we have constructed and keep constructing. The only way to make the world a kinder place is to champion these lost causes.”—Alaa Abd el-Fattah (October, 2025)1

In October 2023, a Hebrew sign that read “The image of victory is a Gaza empty of inhabitants” was put up in Jaffa. It was spotted by Sami Abu Shehadeh, who later told Belal Fadl about it. After Sinwar’s death, an old recording of his2 started circulating, in which he recounted a story from the chronicles of his foretold martyrdom. He said that Israel will assassinate him, then publish the photo along with a caption that says: “The Image of Victory.”

Through everything that Sinwar read and heard in Hebrew during his very long years of imprisonment and then in Gaza, it seems that the phrase “image of victory”3 had become familiar to him, and that he had come to know what it means to the Israelis. He had come to understand that the Israelis, in a way, and for a very long time, have been on a photography expedition, and that the Zionist project has turned into a renewed search for an image of sorts whose subject must be crafted with great care before the photo is captured.

I resist the urge to resort to disturbing comparisons—comparisons to the fetish of serial killers who collect souvenirs from the scenes of their crimes, for instance, or to the art world—and I try to trace this tradition back to its origins. My memory can’t reach further than a photograph by one of their military correspondents, of five paratroopers at the Western Wall—a romantic image of conquest. On the eve of June 5, 1967, it wasn’t possible for an Israeli to articulate an “image of victory” phrase envisioning that which they would acquire over the ensuing six days. That victory surpassed their dreams and our nightmares; a victory that photographs couldn’t accommodate. Especially the artistic, professional photographs which, in retrospect, came to be considered images of victory. Those who crafted the subjects and aesthetics of such photographs with great care were the photographers themselves, but only during the shoot; as for those who had unknowingly prepared the remaining elements of the images before the photographs were taken—elements including our soldiers, herded in their underwear—they were political and military leaders of the highest ranks in Cairo, Damascus and Amman.

That early image of victory—and this was narrated by a middle-ranking Egyptian officer in his eyewitness testimony of the sight of his fellow captives—will draw part of its ‘shock-and-awe’ effect from its dizzying, eerie evocation of the scenes of arrayed prisoners of war depicted in ancient Egyptian murals; images of the Pharaoh’s victory. Extravagant images, costly, confined to spaces of a religious, otherworldly nature; images whose conditions of production would soon be obsolete, and whose revival and subsequent immortality would only be realized thousands of years later. In more recent centuries, the function later inherited by the modern image of victory was performed through more concrete and material traditions, such as the delivery of enemies’ severed heads or ears preserved in salt. Those traditions were living their final days in the same century that would witness the birth of modern photography, as was the public display of disciplined and punished bodies, when the condemned, like Christ, were tortured and killed a thousand times before everyone’s eyes: a live image of the ruler’s victory. One of the factors that accelerated the abandonment of such spectacles was that the excessive brutality of the executioners would sometimes backfire, leading the masses to sympathize with the man or woman being tortured to death.

Photo: Detail from the Abu Simbel Temples—among the few remaining sites of historic Nubia—depicting the Pharaoh’s Nubian captives.

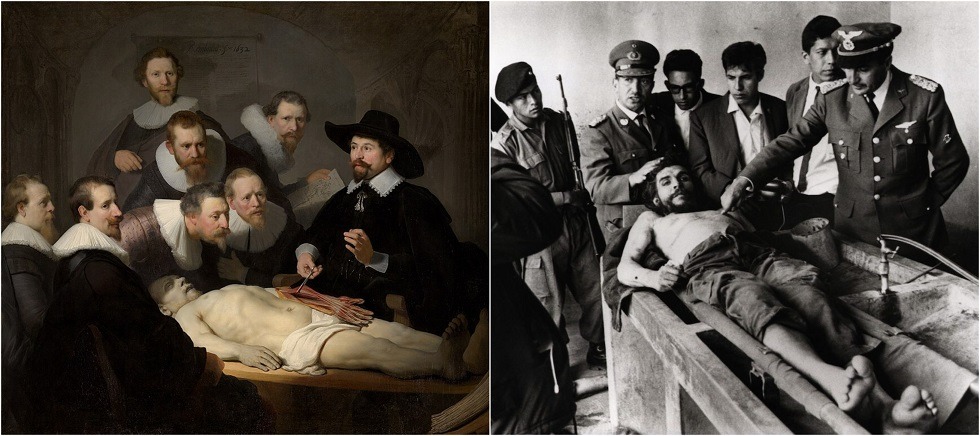

Also in 1967, the posters of Moshe Dayan were plastered on the bedroom walls of American youth and teenagers, and the photo of Guevara lying supine amidst his killers—resembling Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp”—was distributed to news agencies. Proof of death as an image of victory. Soon enough, the Israeli hero’s picture was taken off the walls, perhaps the same way pictures of celebrities are removed to make room for new ones, and perhaps after the young’s excitement had waned upon realizing the triviality of victory in a one-sided war—a triviality that, to us, does nothing to diminish the severity of the catastrophe. As for the icon of the fallen hero, it conquered so much more than bedroom walls, until those who truly knew its subject and considered him one of their own became a minority longing to tear down those images obscuring him.

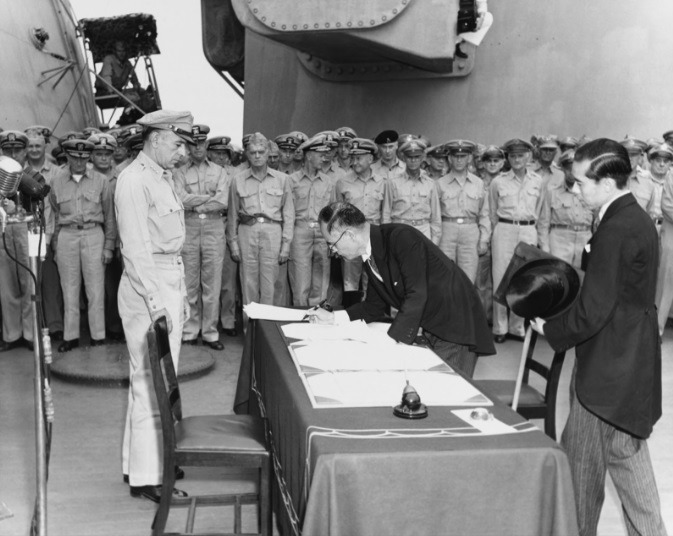

Photo: Shigemitsu signs the Instrument of Surrender, marking the end of World War II.

Documents of surrender are images of victory. In addition to the document itself as an image, and regardless of its name, which might not openly mention surrender as it does in the case of Japan and might instead take the form of a trade agreement or a peace treaty, the image of the event—the act of signing—provides the required visual declaration. Images of victory are not documents of surrender.

Images of victory are ephemeral, and mutable in nature.

We know this because our own images of victory soon brought us pain. It didn’t take too long for us to realize that they did not actually mark a happy ending. Images of jubilant revolutionaries on the streets, where they had previously not been allowed to gather or even be. Images of teeming crowds coming together, causing the viewer to tingle and shiver. “Behold and look at the battleship burn!” Images of the Canal Crossing, which we would later learn—in a double-sided, complex, malicious sense—were actually images of a televisual war, where real fighters in the beginning of a protracted war of liberation were intended to be no more than mere actors, and the war no more than a one-act play. Images of the Palestinian October, in the Gaza ‘envelope’ then in Gaza itself, upon the fighters’ return with their captives.

Photo: The October 1964 Revolution in Sudan

For the cinephile, there is a rather esoteric image of victory in a film that angers many fans of Chris Marker, who is said to have withdrawn Description of a Struggle (1960) from movie theaters after June 1967, when it became clear to him that Israel was using it as propaganda. This wouldn’t, however, undo the effect of that moving image on me, when I made a point of watching the film/Israel with the eyes of an alien, which allowed me to keep anger at bay, and to stare at the tragedy and let it sink in until I could fully absorb it. The scene is a loud and joyful one, where groups of Mizrahi Jews face the camera as they celebrate a religious occasion, their procession traveling along a mountain path. Israel is so young, and these happy, simple people are euphoric with freedom in the land of their dreams, having survived (real, imagined and staged) persecution and pogroms in “the diaspora,” in “exile.” This was their image of victory, in which—for one extremely difficult moment—I was able to identify with them, to empathize with them, to rejoice for them, only to dissociate in the very next moment, returning to myself. The distance then grew and kept growing as I witnessed the magnitude of their actual defeat, of which they are yet unaware: Those ‘survivors’ were destined to become the oppressors, perpetrators of new pogroms and genocides, seekers of the gruesome and atrocious. In this image of victory, where victory supposedly belongs to the oppressed, lies the essence of the great tragedy known as Israel.

Could a depopulated Gaza not be brimming with ghosts? Ghosts like those that trouble the new residents—slowly instilling fear and, ultimately, madness—in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), a film haunted by the spirits of America’s exterminated natives? In Susan Sontag’s Promised Lands (1974), an Israeli soldier with severe PTSD has lost his mind and his peace. In the film, too, is a terrible Israeli image of victory, an open display in the arid expanses of the Golan of charred soldiers’ corpses in horrific poses, like statues eternally screaming in unearthly torment, abandoned atop their tanks. Is it possible, then, not to imagine the Israeli soldier as though he has suddenly turned into a Syrian one who managed to survive, with his body intact, that which had befallen his fellow soldiers the year before? Or an Egyptian one during the Six Days in the Sinai desert, where similar horrific scenes are described in Darraz’s novel? Sontag’s camera leaves neither the “victory” nor the “promise” unquestioned.

The banality of victory, and the speed with which its images mutate, constitute part of the meaning encapsulated by the powerful finale of Lion of the Desert (Moustapha Akkad, 1981). The Italian colonel walks away and women’s ululations rise as Omar Al-Mukhtar hangs on the gallows; he walks away and he grows smaller and smaller until he is all but lost—vanquished, along with his victory. The military-colonial killing machine within him succumbs to a feeble, treacherous human sentiment that peeks in, confusing him, weakening him, tainting his triumph beyond recognition.

Could a drone muster any of this as it edges away, about to kill the target it had guided its controllers to? When exactly did those who posted the shots begin to get flustered; to register the connotations that had leaked out of the video, running amok, ruining the image of victory? Did they really regret it? Did they question one another, lamenting the missed opportunity of capturing a ‘better’ image of Sinwar—hiding, surrendering, or perhaps as a mere corpse? This time, perhaps thanks to the blindness of a high-tech device—one that monitors and kills and swerves away at the right moment to dodge a vertical body hurled in its direction—the final moments of Sinwar’s life have made their way into our collective memory and conscience with a transcendental, almost supernatural force and a sublime magic that renders technology powerless and ideology irrelevant; forever etched across our retinas. Where, I wonder, does the cunning strength of this moving image—with its numbered seconds—lie? And where does it derive its massive, multi-dimensional, multi-directional impact? Is it its straightforward simplicity, bordering on poverty? Its appalling austerity, which stands in stark contrast to the obscene wealth and advancement presented in the murderous, image-recording device? There is no doubt that this is one clue we can follow to make sense of that image, to learn its lessons, to not allow it to disappear in a shroud of mystical, iconic enchantment.

The man holds a stick, or an object resembling a stick, that he has likely gleaned from the sprawling fields of rubble that Gaza had become. It is as though he is balancing it with his left hand—his right arm, now out of service, had passed it the torch—then it appears that he is in fact positioning it with extreme focus and a strange calmness; a perfect fusion of composure, boyish mischief, deep-seated sarcasm and utter defiance. With that object, this human form—drenched in dust along with his stick, to the extent that the publishers of the image had to delineate their shapes using special programs—faces an omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient machine. We don’t know if he thinks it’s pointing a camera or another weapon or both, but he takes his time—intervening in the mise en scène and stealing the weapon, jujutsu style, consciously and unconsciously—to throw his stick at it with the highest possible level of precision and power, and with no clear hope of actually hitting it, let alone stopping it. Suddenly, the hadith advising Muslims on the sound way to behave on the Day of Judgment takes on new meanings: If the Final Hour strikes while you have a stick in your hand, throw it in the direction of the enemy. If you are entirely unarmed, spit at them. If your mouth is dry, smile in mockery, and if you can’t, then shoot them a look of contempt. Hope—in its common, straightforward meaning—is not what’s at play here. Hope amidst the remains of that destroyed house is sheer refusal: to the end, and with a quiet, indifferent, disdainful, confident determination; a confidence with semi-secret sources, to the spectator’s chagrin or awe. Hope is the stone thrown at the tank, and now this primitive, improvised weapon against the most cutting-edge model of robotic weaponry, capable of overtaking us wherever we might be, like certain death, as if by divine decree. In this sense, Sinwar represents more than a Palestinian or a colonized person resisting to the last breath: He is us, inhabitants of an age steeped in rapid and advanced capitalist destruction, which diligently—in a dazzling accumulation of power and wealth and comprehensive surveillance—pits itself against the rest of us: the underdeveloped and superfluous; defilers of the pure beauty of ultra-sleek, ultra-sophisticated weapons; impingers on the gaze of the privileged, the ultra-neat. He is us—unarmed, stateless, homeless, unprotected—yet unable to remain quiet, to refrain from disturbing the peace.

With the spectacle of his martyrdom, even with the moving picture abruptly cut, Sinwar avenged wholesale, unceremonious assassinations, meted out by highly penetrative forces (infiltrators, booby trappers, bunker busters) that murdered en masse other leaders, thus depriving them of the chance to die in action. He saved himself from death without a fight, as he had insinuated in that recording, expressing fear of a fate like Khalid ibn al-Walid’s, who died in bed “like a camel,” or Frantz Fanon’s, who missed the final battle in Algiers as he lay sick and dying in an American hospital, and had to make do with composing his final work, about those whom he called Les Damnés de la Terre, with their violence and madness, striving for healing and salvation. Sinwar died an ordinary fighter, so ordinary that his enemy merely stumbled upon him. He thus placed his image alongside the images of ordinary Palestinians burnt alive and bombed and shot and starved to death, Palestinians upon whom humanitarian aid descends to sometimes kill them as well. He placed his militant steadfastness alongside the many forms of their daily steadfastness. He has preceded them: to a Palestine, or to another paradise, or to an eternal rest, fleeing their reckoning and moving forward to a Day of Reckoning he believed in, in a world that wouldn’t allow him to believe in democracy.

Perhaps Sinwar, too, was a political bully in his lifetime. Perhaps he killed other Palestinians whom he judged to be collaborators or rivals, perhaps he blessed the brief Palestinian civil war from his prison cell in 2007, perhaps many Palestinians consider October 7 to be a one-man decision that has thrown them straight into perdition. In his final scene; his final, glorious, miniscule battle, Sinwar resisted Israel, resisted the meaning intended by its image of victory, and resisted our own readiness to dehumanize him, evading the complexities of our impossible situation: He was born to refugees in Gaza five years before it was occupied by Israel, an occupation in whose shadow he grew up, studying science and choosing Islam as a path of struggle, before the Intifada broke out. One year after the execution of his grandest, most perilous, most intricate and most spectacular ijtihad, throwing that stick was his final, humble attempt at resisting the monster. He was making a very complex statement; in one sense it is a wry paraphrasing of Mahdi Amel’s famous adage: “You are not defeated so long as (your enemy needs to capture your final image while) you resist!”

Does the victor need an image of their victory? How many images do they need?

When we are victorious, it will be a feast and our dead will dance. Sinwar will dance with his stick. And the image of victory? If necessary, and if we really want to fight, there will be images of tribunals in that land from the river to the sea, where proceedings will take place in Arabic and Hebrew. There will be other images, and in all of them there will be ruins: the ruins of nationalism, of colonialism and capitalism and patriarchy, the ruins of barbarism, the ruins of history—a history where violence and oppression reigned, and where images of their power were worshipped and glorified.

- This text was originally published in Arabic following the death of Yahya al-Sinwar in October 2024. This epigraph is from the first published interview with Alaa Abd el-Fattah after his release from a long imprisonment. ↩︎

- The viral clip was taken from the full-length recording of a press interview in May 2021 (at 84:00). ↩︎

- In the Israeli film Image of Victory (Avi Nesher, 2021), which centers on the 1948 war and is often described as a balanced work that empathizes with all parties, the protagonist in search of the “image of victory” is, ironically, an Egyptian photographer accompanying a group of volunteer Egyptian fighters tasked with protecting Palestinians, who hopes that the war and his ability to capture quality propagandist photographs would help him achieve his ambition of becoming a filmmaker. ↩︎

علّق/ي